It’s called collaborative consumption, (or the sharing economy) and it’s changing the way we work, play, and interact with each other. It’s fueled by the instant connection and communication of the Internet, yet it’s manifesting itself in interesting ways offline too.

The collaborative consumption movement empowers people to thrive despite economic climate. Instead of looking to the government or corporations to tell us what we want or create a solution for our problems, we take action to meet our own needs in a creative fashion.

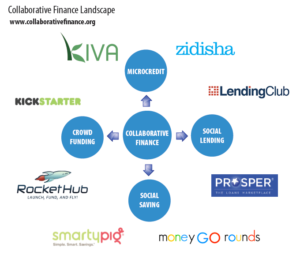

The term collaborative finance is used to describe a specific category of financial transaction which occurs directly between individuals without the intermediation of a traditional financial institution. This new way to manage informal financial transactions has been enabled by advances in social media and peer-to-peer on line platforms. The wide variety of Collaborative Finance resources may vary not only in their organizational and operational aspects, but also by geographical region, share of the financial market etc. It is precisely this heterogeneity that enables the informal savings and credit activity to profitably reach those income-groups not served by commercial banks and other financial institutions. It is their informality, adaptability and flexibility of operations – characteristics which reduce their transactions costs and confers upon them their comparative advantage and economic rationale. Collaborative Finance is characterized by highly personalized loan transactions entailing peer-to-peer dealings with borrowers and flexibility in respect of loan purpose, interest rates, collateral requirements, maturity periods and debt rescheduling.

Following are the features of Collaborative Finance that make it attractive to low income households:

- It does not require a license – most informal suppliers work without an operating license to supply money.

- It facilitates very small savings – small amounts that can be saved daily.

- It is non-profit motivated – profit, if any, is ploughed back into the community and its members.

- It has strong organizational structures – community initiatives are usually part of the well setup people’s organization.

- It has multiple proprietorship – proprietorship lies not with one or two persons, but the group as a whole.

- It does not need collateral – collateral and guarantees of repayment is ensured by, for example, peer pressure.

- It provides localized services – at the door step of the household, or within the community itself.

- It has specific borrowers identified – most of whom are members of the community.

- It has personalized services – the terms and conditions under which loans are given are tailor-made to the needs of its members.

- It has close informational links – between members that ensure repayment.

- It has high repayment rates – the average repayment rates for informal initiative has been above 95%.

- It facilitates reciprocation of credit disbursal – there is a give-and-take attitude, where borrowers and lenders interchange their roles.

- It is not regulated by the central bank – with respect to limits and restrictions, reporting requirements etc.

- It encourages community participation in other fields of development – the participatory approach of informal initiatives is easily replicable to a wide range of other community development issues.

MICRO LENDING AND SOCIAL MEDIA

Microfinance is the provision of financial services to low-income clients or solidarity lending groups including consumers and the self-employed, who traditionally lack access to banking and related services. More broadly, it is a movement whose object is “a world in which as many poor and near-poor households as possible have permanent access to an appropriate range of high quality financial services, including not just credit but also savings, insurance, and fund transfers.”. Those who promote microfinance generally believe that such access will help poor people out of poverty.

Microfinance agencies provide loans to small businesspeople who often can’t meet the strict credit terms of large banks. Either these entrepreneurs don’t have the capital or the cash to back the loan. Or as the large banks argue, their credit needs are too small.

With banks out of the picture, microlending agencies step into the role usually held by the imperfect combination of relatives and often predatory money lenders. Microlending is most often associated with the developing world, but agencies have begun working in industrialized countries.

The Grameen Bank, the world’s first microfinance institution, was born in Bangladesh in 1983 by Mohammed Yunus, an economics professor who launched it to help alleviate rural poverty by providing much needed funds to entrepreneurs to grow their businesses. Not only would the poor repay these loans, Yunus argued, but the Grameen Bank’s lending style would become a sound investment. In 2006, Yunus won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts. By 2008 Grameen Bank had lent $7.6 billion.

As the internet age hit, microlenders began looking for ways to replicate the Grameen Bank’s success online. With the rise of social networking, especially peer-to-peer media, these lenders found their answer. One of the first microlenders to have an impact over the internet is the US-based Kiva, which began a few years after a couple traveled to East Africa in 2004. Kiva claims to be the world’s first “person-to-person micro-lending website.” The question, however, remains: Will social media help create a sustainable market for microfinance?

SOCIAL LENDING

Social lending sites, also called peer to peer lending sites, provide borrowers and lenders a marketplace to cut out the costs and hassles associated with financial intermediaries. Social lending sites connect individual lenders and borrowers through a social network that is streamlined, efficient, legally formatted, profitable and most importantly – helpful. The growth and maturity of the social lending industry in the last couple of years has made it a viable alternative to traditional bank and personal loans. A primary reason for the solid growth of social lending is that borrowers on social lending sites can find better loan rates than they can find through other borrowing avenues. It is also easier for individuals to borrow smaller amounts of money. Whether a borrower is saving for college, a vacation or to start a new business, borrowers can shop their loans and start receiving bids on the same day.

In Kiva‘s website you can lend to someone across the globe who needs a loan for their business – like raising goats, selling vegetables at market or making bricks. Each loan has a picture of the entrepreneur, a description of their business and how they plan to use the loan so you know exactly how your money is being spent – and you get updates letting you know how the entrepreneur is going.

The best part is, when the entrepreneur pays back their loan you get your money back or use it for another loan (I like this idea because you can give a small loan once and use the same amount over and over)- and Kiva’s loans are managed by microfinance institutions on the ground who have a lot of experience doing this, so I suppose you can trust that your money is being handled responsibly.

Kiva allows a potential lender to browse profiles of people needing finance. If a entrepreneur is selected and a loan made, Kiva then allocates the funds to one of its microfianance partners, an agency working on the ground. The recipient will then repay the loan, usually at interest. (The use of interest is controversial, but common, within microfinance.) Kiva’s site allows lenders to follow the money throughout the loan process, keeping tabs on repayment and other personal updates. This has caught on to other lending sites.

What helps drives these sites isn’t just the loans; it’s the methods used to make the funds available. “Social networks are important,” writes Jon Camfield in his self-titled blog. “Trust — more commonly called social capital in this situation — is the strength and number of interpersonal connections. Facebook, Twitter and the like are convenient ways to map out these connections (within a connected group of people), but hardly replace them.”

This is by no means new in development theory, and is often portrayed as either the keystone to successful development or a red herring (and to be fair, it’s probably both). Social Networks also provide a second important role. Beyond increasing trust to enable all sorts of transactions, and providing back-channels to smooth those along, they also improve (if not outright cause) technology diffusion. Spread throughout a network will be innovators, experimenters and early adopters who create, tweak and test new ideas, and then begin to spread them by word of mouth as well as through successful implementations.

The marriage of micro lending and social media works two ways. First it allows a disparate group of people, perhaps the entrepreneurs, to communicate and become organized. Secondly, it allows them to reach out and relay their message with the larger world. Microlending organizations have latched on to this, leveraging technology to make sure potential lenders can put a face to recipients’ stories. Perhaps these personal bonds originate from the Grameen Bank, which began lending funds on the basis of trust and used peer pressure to insure the loans were repaid. Or, perhaps microlenders online use interpersonal connections as a bulwark against compassion fatigue.

Prosper connects people who are looking to invest with people who are in need of a loan, and has built a community around the system of mutual connections. People who are in need of loans are able to receive a personal loan at a fixed rate, which start as low as 7.5%APR. For those looking to invest, they can offer a loan to an individual borrower and receive an estimated return of 10.4%, which is higher than other investment alternatives. With their innovative peer-to-peer lending system, borrowers can end up taking small loans from multiple lenders, in amounts as small as $25. Borrowers must have good credit history with a score of at least 640, and lenders have access to each borrower’s credit history and reason for wanting the loan.

CROWDFUNDING

Crowdfunding has some similarities to the peer-to-peer lending sites, such as Prosper.com, that arose several years ago, but some important differences as well. Both types of sites allow individuals to solicit financing from others for any purpose. But while peer-to-peer lending typically focuses on one individual lending to another, crowdfunding—as its name implies—aims to reach a funding goal by getting many investors to put in small amounts.

A crowdfunding site can be a great way to simplify the process of seeking financing from, say, family and friends. And until now, most business owners using the sites have been looking for very small amounts ($10,000 or less). However, according to the Journal, the sites are beginning to enable larger transactions as more business owners are turning to them.

Kickstarter aims to let creative people of all kinds — journalists, artists, musicians, game developers, entrepreneurs, bloggers — raise money for their projects by connecting directly with fans, who receive exclusive access and rewards in exchange for their patronage. Like Josh Freese and Jill Sobule, the site allows creators to have multiple tiers of rewards (e.g. $20 for the book, $50 for signed copy) with optional limits for each.

The model is simple: a project creator sets a fundraising goal, deadline, and an optional set of rewards for backers. If the goal’s reached by the deadline, then everyone’s charged via Amazon Payments and the backers get their goodies. If the goal’s not reached, nobody’s charged. It’s all or nothing.

One of Kickstarter’s best-known success stories is Diaspora, the open-source social network that some are hoping will become an open alternative to Facebook. The startup managed to raise $100,000 in a matter of weeks, thanks in part to some attention from several leading tech blogs. But plenty of other Kickstarter projects are somewhat less glamorous or high-profile.